Defense Counsel Journal

Lessons From a Year in Crisis: Do’s and Don’ts of Crisis Management

Volume 89, No. 1

January 26, 2022

Claudia V. Garcia

Claudia V. Garcia

Claudia V. Garcia

Claudia V. Garcia is Corporate Counsel, Commercial at Exelixis, Inc. In this role, she helps colleagues navigate the complex legal and regulatory landscape as they work to develop medicines for difficult-to-treat cancers. Prior to joining Exelixis, Claudia represented major pharmaceutical and medical device companies in products liability cases involving prescription and over-the-counter medications, medical devices, and consumer products. She received her J.D. from the University of San Francisco School of Law, and her B.A. from the University of California, Davis.

Kaitlyn E. Stone

Kaitlyn E. Stone

Kaitlyn E. Stone

Kaitlyn E. Stone is an associate Faegre Drinker’s Product Liability and Mass Torts practice group. Kate’s practice includes defense of clients in various mass tort, intellectual property, and complex litigation matters, with a focus on defending the interests of major pharmaceutical, medical device, and med tech companies, and companies in agribusiness and chemical industries in product liability cases. She has experience ranging from individual cases to class actions, and the majority of her practice focuses on multidistrict litigations and coordinated state proceedings. Kate also maintains an active pro bono practice, focused primarily on securing criminal expungement for indigent clients and veterans in New Jersey.

Michael C. Zogby

Michael C. Zogby

Michael C. Zogby

Michael C. Zogby is a partner and deputy leader of the nationally-ranked Product Liability and Mass Torts group at Faegre Drinker. Mike also serves as co-chair of the firm’s Health & Life Sciences Litigation team. His trial practice includes the defense of global clients in highly-regulated industries in cross-border, products liability, complex litigation, mass tort, and intellectual property actions filed by consumer and government parties. He counsels clients in the United States, Asia, and Europe on data privacy, governance, cybersecurity, and crisis management issues, and he coordinates cross-border trial strategy and discovery involving multidistrict and aggregate proceedings. He serves on the faculty of the National Trial Advocacy College at the University of Virginia School of Law and as a trustee of the Trial Attorneys of America and Trial Attorneys of New Jersey.

The views and opinions expressed within this article are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of their employers.

CRISIS loves company. Like many of the readers of this publication, we transitioned from trials and in-person litigation activities to spend the last 18-plus months focusing and counseling on crisis management issues. Unlike others, however, we had occasion to do so not only in light of the COVID-19 global pandemic, but because we partnered with ten in-house counsel and forensics/public relations professionals throughout 2020 and 2021 to dissect, publish, and speak on issues related to effective crisis anticipation and resolution techniques, as well as on the intersection of crisis, cross-border disputes, and litigation.

Through this process, we have identified a collection of pragmatic “dos” and “don’ts” for organizations faced with business crises. We share these recommendations as a reference guide as we approach the two-year anniversary of many of us working remotely. These can be applied to any business or risk management crisis, and they should be incorporated into our regular practices and response processes.

I. DON’T Take a One-Size-Fits-All Approach

In a pie chart tracking the general discourse regarding crisis management strategies, crisis management plans – or CMPs – would take up a significant slice.1See, e.g., J. Michael Rollo and Eugene L. Zdziarski, “Developing a Crisis Management Plan,” in Eugene L. Zdziarski et al., Campus Crisis Management (Wiley, 2d. Ed. 2020).

In the cybersecurity space, via Executive Order No. 14028 (“Improving the Nation’s Cybersecurity”), the White House recently tasked the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) with developing “a standard set of operational procedure (i.e., playbook) to be used in planning and conducting cybersecurity vulnerability and incident response activity.”2Exec. Order 14028, 86 Fed. Reg. 26633 (May 12, 2021), available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/05/12/ executive-order-on-improving-the-nations-cybersecurity/.

In November 2021, the CISA published the Federal Government Cybersecurity Incident and Vulnerability Response Playbooks, once again putting crisis management planning documents in the forefront of minds considering crisis response techniques.3See Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, Federal Government Cybersecurity Incident and Vulnerability Response Playbooks, at 7 (Nov. 2021), available at https://www.cisa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Federal_Government_Cybersecurity_Incident_and_Vulnerability_Response_Playbooks_508C.pdf (“[p]reparation [a]ctivities” include “[d]ocument[ing] incident response plans, including processes and procedures for designating a coordination lead” and “[p]ut[ting] policies and procedures in place to escalate and report major incidents and those with impact on the agency’s mission”).

While it is true that the importance of planning for crises cannot be overstated, the phrase “crisis management plan” suggests that with enough foresight, focus, and resources, a company may divine one plan ready to be implemented at the first hint of any crisis to neutralize the threat entirely.

However, don’t think that a single crisis management plan will do the trick for each and every crisis on the horizon. Adopting a one-size-fits-all approach to crisis response planning will not only produce an inadequate strategy for future crises, it will set unreasonable expectations for the nature of business crises themselves.

Crises are fluid, and the best crisis management plans are flexible and made to change in response to the nuances of a given problem. Rigidity is the enemy of effectual crisis management.4See generally Anne H. Reilly, Preparing for the worst: the process of effective crisis management, 7 Industrial & Environmental Crisis Q. 115 (1993).

CMPs with built-in flexibility, adaptable to the particular variety of challenges that may arise for a given company, are key. Multiple avenues of action, some to be implemented parallel to others and some to serve as alternative options, are part of an effective CMP, which should set forth the list of viable options that may best respond to a particular crisis. Each crisis is unique, and the company’s approach to managing the crisis should be specifically tailored to the problem presented. Put another way, crisis management should always be bespoke – not off the rack.

II. DO Anticipate & Avoid

Planning for a crisis is only half the battle – and a reactionary approach might eliminate options or put you behind in the response plan. The best crisis-related strategies involve anticipation of potential catastrophes as a means of avoiding them altogether. Anticipation and avoidance are the hallmarks of premier crisis management.5See John F. Savarese, Handling a Corporate Crisis: The Ten Commandments of Crisis Management, 27 Rev. Banking & Fin. Servs. (2011) (“Many crises can be anticipated, at least generally.”).

Without intention, the human mind is not inclined to see, let alone foresee, problems. Thanks to a phenomenon known as normalcy bias, the mind has a tendency to expect things to continue to occur in the future as they typically have in the past—to assume that matters will proceed “normally.”6See Leonard Mlodinow, Subliminal: How Your Unconscious Mind Rules Your Behavior (2012); Linda Ross Meyer, Suffering and Judging in the Princess and the Pea, 30 Quinnipiac L. Rev. 489, 501 (2012); see also Barry Ravech, Book Review, On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You're Not, 93 Mass. L. Rev. 364, 367 (2011).

This bias may lead one to underestimate both the likelihood of a crisis occurring, and how bad the disaster may be when it does arise.7See David B. Graham and Thomas D. Johns, The Corporate Emergency Response Plan: A Smart Strategy, 27 Nat. Resources & Env't, at 6 (2012).

We are familiar with examples of normalcy bias from recent history and popular culture. For example,

Normalcy bias was demonstrated by the statements of BP's ousted CEO, when he stated that “the Gulf of Mexico is a very big ocean. The amount of volume of oil and dispersant we are putting into it is tiny in relation to the total water volume.” Normalcy bias [was] further exemplified by the response of the Costa Concordia crew. After the ship struck the rock near Giglio Island, passengers were reportedly told to return to their staterooms. About an hour passed before the order to abandon the ship was issued, possibly contributing to the loss of thirty-two lives as well as the $570 million vessel. Thus, normalcy bias will delay critical actions and place the response team behind the power curve; a position from which it is unlikely to recover.8Id. (internal citation omitted).

Research suggests approximately 70% of people will succumb to this bias in a crisis situation.9See Amanda Ripley, How to Get Out Alive, Time 58, 60 (May 2, 2005); see also Haim Omer and Nahman Alon, The Continuity Principle: A Unified Approach to Disaster and Trauma, 22 Am. J. Comm. Psych. 273 (1994).

Identify strategies that enable you to forecast potential issues for your company. The bad news on this front is that there is no crystal ball for future threats or catastrophes. The good news is there are no shortage of tools available to companies seeking to mine for potential threats looming in the distance. These anticipatory exercises may help a company’s team members overcome normalcy bias, enable the organization to identify and analyze potential threats before they occur, and vet the strength of the solutions created to address and avoid them.10Recently, Edwin Deitel considered what “[d]ecision-makers must [do to] surpass common judgment biases,” including:

•People tend to hold positive illusions that lead them to interpret events in an egocentric manner and to undervalue risks.

•People have a natural tendency to discount the future, which reduces their willingness to invest now in order to prevent a disaster that may be quite distant and vague.

•Most people will discount the need for fundamental change.

•People tend to ignore errors of omission or the harm that comes from inaction, and pay greater attention to harm that comes from action.

•People tend to try and maintain the status quo, creating a barrier to the concrete and often large-scale changes that are needed to head off predictable surprises.

•People tend to have optimistic illusions about the future that prevents them from envisioning catastrophe.

•Most people are willing to run the risk of incurring a large but low-probability loss in the future rather than accepting a smaller, sure loss now.

J. EDWIN DEITEL, DESIGNING AN EFFECTIVE CORPORATE INFORMATION, KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT, AND RECORDS RETENTION COMPLIANCE PROGRAM, § 14:19. “Anticipating and Preventing Crises” (West, Aug. 2021). For “organization[s] to avoid predictable surprises”, the author recommended:

•Scan the environment and collect information regarding all significant threats.

•Integrate and analyze that information from multiple sources within the organization to produce insights that can be acted on.

•Respond in a timely manner and observe the results of the response.

•Reflect on what happened and incorporate lessons learned into the institutional memory of the organization, in order to avoid repetition of past mistakes.

Id.

Extensive literature exists on anticipatory tools available to businesses. For example, red teaming – a collection of flexible cognitive processes aimed at asking better questions, challenging explicit and implicit assumptions, and developing alternatives to challenge existing policies or procedures – has garnered attention during the pandemic.11See, e.g., United States Department of Defense, Red Teaming, Past and Present – Case Studies: Field Marshal Slim in Burma, T.R. Lawrence in World War I, Operation Iraqi Freedom, Decision-Making Theory, Challenging Organization’s Thinking (2017).

The concepts of either expanding the exercise with a blue team (a team designed to defend existing policies and procedures against the red team’s attacks), or condensing the exercise with a purple team (utilizing the same team to act as both attackers and defenders of policies, seeing all sides of the relevant issues) are also gaining in popularity. This collection of tabletop exercises encourages a business team to approach potential problems from unexpected angles and identify any and all possible solutions to them. Premortems, thinking about a CMP’s solutions to a given problem from the hypothetical vantage point of assuming the solutions have already failed, are also gaining traction, as are a variety of approaches to trend forecasting.12See generally David Gallop, Chis Willy and John Bischoff, How to Catch a Black Swan: Measuring the Benefits of the Premortem Technique for Risk Identification, 16 J. Enterprise Transformation 87 (2016).

These may also enable a company to predict potential catastrophes coming down the proverbial pipe.

Finding strategies to guide your company in its efforts to anticipate crises is not especially challenging. The challenge lies in selecting the right strategies for your company. Whatever the name, or present popularity, the bottom line on anticipatory tactics is: Choose the one that will best help your particular business forecast potential future problems.

III. DON’T Think Crisis Happens in a Vacuum

When faced with a looming threat or high-stakes disaster, it can be easy to get lost in the catastrophe and lose sight of the larger picture. But crises do not respect geographic boundaries, and—as the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated—the worst catastrophes often spread across multiple locales.

Don’t forget to think about the bigger picture. The company’s present crisis may presently be occurring in the United States, but might it or the company’s response thereto have implications for the company’s parent or affiliates in Europe or Asia down the road? The business’s current catastrophe might involve an incident at a single facility requiring the roll-out of human resources support on the ground, but might it result in later litigation implicating other departments within the business?

As the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated, a variety of litigation can and will arise from a large-scale crisis. The year 2020 saw a wide array of litigation filed, including by customers against cruise lines, patients against nursing homes, employees against employers, and patrons and employees against restaurants and bars.13See Amanda Robert, What Types of Lawsuits Were Filed Over COVID-19 in 2020?, ABA Journal (Jan. 4, 2021), available at https://www.abajournal.com/news/article/law-firms-schools-identify-lawsuits-filed-over-covid-19-in-2020; Amanda Bronstad, Lawsuits Filed in 2020 Over COVID-19 Were Diverse, but Limited, Law.com (Dec. 29, 2020), available at https://www.law.com/2020/12/29/lawsuits-filed-in-2020-over-covid-19-were-diverse-but-limited/.

A true crisis will feel all-encompassing and likely overwhelming, but do not permit this sensation to produce tunnel vision. Crises, and a company’s response to them, have a tendency to birth new and related problems. Always consider the problem and its solutions in the context of the larger business plan, client concerns, and the company’s global priorities.

IV. DO Pick the Right Players

Crisis anticipation strategies and CMPs are only as good as the team that executes them in real time. These theories and ideas need to be animated by a carefully selected group.

Be sure to assemble the right team, with members from multiple departments and with varying backgrounds, to stand at the ready to tackle crises. The team’s purpose is to shepherd the business’ response to a problem at both macro and micro levels. To do so, the team must be prepared to coach the organization’s individual employees through the problem, while simultaneously steering the company’s ethos, and perhaps even its clients or customers, through the process.

Who should be on the team? Like all aspects of crisis management, the team’s members should be tailored to the needs of the company and the kinds of crises that confront it. The most successful team will capitalize on the diverse skills of their organization’s talent – derived both from in-house and outside vendors.14See Sujin Jang, The Most Creative Teams Have a Specific Type of Cultural Diversity, Harvard Bus. Rev. (July 24, 2018) (“Culturally diverse teams, research shows, can help deliver better outcomes in today’s organizations.”).

Popular players include members from the following departments: in-house counsel, internal corporate communications, administrative support, human resources, and IT. Also keep in mind data preservation requirements and the importance of documenting steps taken to serve as breadcrumbs if you need to retrace your steps or justify reasons for action.

In addition, you should encourage and benefit from the diversity within your organization. Remain mindful of your personnel’s diverse backgrounds and experiences when assembling your teams. A team with varying experiences and viewpoints will come together to produce crisis management approaches that are culturally sensitive and, therefore, more effective.

V. DON’T Fix it and Forget it

While it may be tempting to say that nothing positive emerges from a business crisis, there is always one silver lining: Each crisis presents an opportunity to learn. The only thing worse than a crisis is facing the same crisis twice without proper preparation.

Don’t fix a crisis and forget about it. When the storm clouds clear, dig into what happened so as to mine the situation for enhanced institutional knowledge. Study the problem, including what worked and what did not work when it came to solutions, in order to be better equipped to tackle this issue or a similar issue in the future. In fact, especially study the failures. While the temptation will exist to celebrate the victories over the catastrophe – and positive reinforcement for these successes is encouraged – missteps and missed opportunities present the richest ground from which to cultivate a greater understanding of the crisis and the company’s best response to it.

Many organizations find postmortems to be a useful tool in analyzing a crisis in hindsight. Use of tools like this one ensure analysis of the past problem is productive and thorough, instead of an exercise in mere Monday morning quarterbacking.

VI. DO Partner for Success

When crisis strikes, it is important to look for the hands reaching out to help. Assembling the right team internally is important but does not complete the roster of crisis team players.

Do not hesitate to bring in outside help to support crisis management operations. Consider collaborating with external vendors in order to increase the value of crisis response or anticipation efforts. The company may elect to include outside legal counsel, security vendors, forensics, and IT support as applicable. The participation of experts and vendors from outside the organization diversifies the crisis response or anticipation team’s perspectives, inviting outside opinions regarding the business strategies and potential threats to the company, into the analysis.

When assembling the right team, we strongly recommend the team include outside counsel, external public relations firms, forensics, and external IT support as needed. In addition, consider whether subject matter experts are needed to support the team’s efforts and whether involvement of a medical adviser, privacy expert, or cybersecurity analyst is warranted.

VII. DON’T Undervalue Culture

Business crises often implicate or affect a company’s bottom line, but don’t neglect the human element involved in these problems and don’t underestimate the importance of values and experiences outside the United States.

While the concept of crisis is a universal one, culture plays a significant role in disaster response.15Richard Levick, Litigation Communications in the Information Age: What Every Lawyer, General Counsel, Communications Officer, and Board Member Should Know, 38 Of Couns. 6 (2019) (“Culture dictates outcomes” and “has an unspoken yet outsized influence on almost all high-profile matters. . . . Great leadership comes from those who understand and appreciate that the culture of the market where the crisis arises has to be the culture of the crisis team.”).

Catastrophes, especially cross-border ones, are likely to involve employees or clients from multiple cultures. When a crisis strikes, people react and recover within the context of their individual backgrounds, viewpoints, and values. Culture influences how one assigns meaning to a given crisis, and it may even affect what qualifies as a crisis or the perceived scale of the problem. Culture also influences how people convey stress through communication and behavior in connection with a crisis event and influences one’s interpretation of what it takes to make him or her feel safe in a catastrophe. As discussed in “Cultural Approaches to Crisis Management,” which is featured in the Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, there is a connection between cultural competency and resiliency. A crisis management plan equipped with cultural awareness and respect for diversity will enable a business to thrive when it comes to addressing the other complications that arise in an emergency. Diversity should be a consideration in all crisis response planning, and an inherent piece of the framework used to develop those plans, too.

VIII. DO Polish Your Crisis

Some of the most high-stakes communications a company engages in occur during times of crisis. Prompt and frequent communication is essential when managing a business crisis. What is said, how it is said, and when it is said are of the utmost importance at times like these.

Keep the company’s ethos and goals front of mind when crafting crisis communications. Engaging an outside vendor may prove useful to help draft the appropriate messaging, avoiding landmines in word choice and tone. Remember that audience considerations are key: In times of crisis, the right communications to clients may differ from the right messaging to personnel. While a single, blanket press release may prove useful in terms of communicating promptly, consider whether multiple communications tailored to each audience might best convey the company’s position in the crisis. Geographic considerations may influence communications choices, too.16See United States Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services, Center for Mental Health Services, Developing Cultural Competence in Disaster Mental Health Programs: Guiding Principles and Recommendations, 17-19 (2003).

When addressing an emergency in multiple locales, it is critical that oral and written communications be available in all languages spoken by the company’s workforce and clients.17See also Y. Siew-Yoong, J. Varughese and A. Pang, Communicating Crisis: How Culture Influences Image Repair in Western and Asian Government, 16 Corporate Communications: An International Journal 218, 236 (2011) (“[i]n a crisis, it is not what is spoken—it is how it is spoken”).

In addition, consider not only the content of crisis communications, but also the channel. As witnessed during the COVID-19 pandemic, some crises will limit the means by which your organization may communicate with employees, clients or customers. Some crises will limit or eliminate your ability to transmit crises communications in-person, even when a face-to-face interaction might prove the most meaningful way to transmit your company’s message. Be prepared to navigate the challenges inherent to limited communication methods and to maximize the benefits of those communications channels still available to your organization.

IX. DON’T Only Think About Crisis in a Crisis

The temptation exists to only think about a crisis while in a crisis. It is easy to focus entirely on the problem while it occurs. Alternatively, there may be a desire to anticipate other possible crises while another one is still ongoing, simply because the urge to avoid disasters altogether is so great in that particular moment. On the other hand, it may be harder to encourage the organization to dedicate time and resources to considering crises in times of calm.

Don’t be complacent or distracted. In this context, timing matters. Focusing wholly on the crisis at hand until it is under control, and analyzing crisis management issues in times of calm, are precisely the separate and distinct strategies needed to ensure a company escapes a present catastrophe with minimal damage and is ready for the next challenge. When assembling annual budgets and calendars, consider the best time for your organization to tackle crisis management issues. While no crisis can be conveniently scheduled, companies can elect when they will dedicate time, personnel and resources to anticipating or planning for crises.

X. DO Pivot, Pivot, Pivot

One of the many challenges in a crisis is the inability to settle in. Effective crisis management is guided by an approach that is malleable and adaptable to the sea changes inherent to largescale disasters.

Be ready to pivot, and pivot again as needed. If a plan is not successfully addressing a problem, change it. If a team addressing a disaster is incomplete, add whomever you need to the group. If a communication issued about the crisis has not landed right with the intended audience, try again quickly. Be prepared to assess the situation and make informed but quick decisions in real time. Agility is a virtue when faced with a crisis. Be ready for the changes, and ready to change with them.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a recent example of the importance of agility in a crisis. Consider the industries, including many companies and manufacturers in the pharmaceutical, medical device, consumer products, machine, and life sciences industries that pivoted to producing personal protective equipment (“PPE”) in response to the pandemic. On March 17, 2020, the U.S. Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services issued a declaration under the Public Readiness and Emergency Preparedness Act (PREP Act) extending immunity from liability for claims of loss caused, arising out of, relating to, or resulting from the administration or use of certain countermeasures, such as respirators and masks, used to combat or reduce the spread of COVID-19. On March 27, 2020, President Trump signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) into law, which provided emergency assistance to those affected by the global pandemic by, among other things, incentivizing businesses to manufacture respiratory protective equipment through extension of certain liability protection to manufacturers of certain devices used in the fight against COVID-19. In response, U.S. companies that are not typically in the business of manufacturing PPE pivoted to produce and distribute this much-needed equipment. This example illustrates how regulatory change may precipitate an opportunity to pivot during an ongoing crisis.

XI. A Trend Emerged in a Year of Crisis

A trend emerged in the last year: doing business in the remote environment. Many of us have worked, or are continuing to work, from home or elsewhere beyond the confines of the office. While shifting to find success in the remote work model was essential for most businesses during the COVID-19 pandemic, it also have given rise to a shift in priorities and potential concerns – namely, cybersecurity and data privacy issues.18See Lakshmi Hanspal, Cybersecurity is Not (Just) a Tech Problem, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Jan. 6, 2021), available at https://hbr.org/2021/01/cybersecurity-is-not-just-a-tech-problem; Mark Hughes, How to Make Cybersecurity a Top Priority for Boards and CFOs, Harv. Bus. Rev. (Jan. 28, 2021), available at https://hbr.org/sponsored/2021/01/how-to-make-cybersecurity-a-top-priority-for-boards-and-cfos.

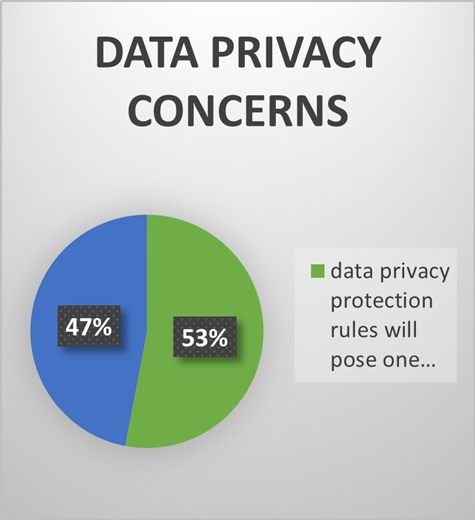

The last year has put an especially bright spotlight on these issues, but this is not to suggest these are new concerns. For the third consecutive year, in the Association of Corporate Counsel’s 2021 Chief Legal Officers Survey, which gathered responses from nearly 1,000 in-house counsel across 21 industries and 44 countries, participants indicated that cybersecurity, compliance, and data privacy top the list of most important issues for businesses. In 2021, for the first time, the majority of participants indicated that cybersecurity is a greater concern than compliance issues. In fact, 53.6% of participants indicated they believe that data privacy protection rules pose one of the biggest challenges to their organizations.

Derived from the Association of Corporate Counsel’s 2021 Chief Legal Officers Survey.

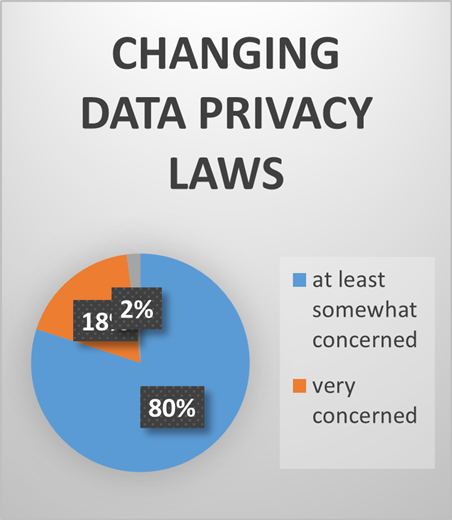

In addition, nearly 80% of participants said they are at least somewhat concerned about changing data privacy laws in the jurisdictions where they do business, while 18% said they are “very concerned” about this issue.

Derived from the Association of Corporate Counsel’s 2021 Chief Legal Officers Survey.

While issues related to cybersecurity and data privacy are not new, they have become especially important in the remote work environment. Ransomware attacks were on the rise last year across all sectors and are becoming more sophisticated by the day. High profile hacks have become a fixture in the evening news, with hacks seen in major industry leaders, like Colonial Pipeline in May 2021, to the federal court system in January 2021. The latter prompted the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to issue an emergency directive and announce new procedures for the filing of highly sensitive court documents (“HSDs”). In the wake of the hack, HSDs were no longer to be e-filed via the CM/ECF system, and instead were to be filed in paper format or via a secure electronic drive, like a thumb drive, to be stored in a stand-alone system by the court.

With the expectation that, at least to some degree, the work-from-home model will persist in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, companies must be laser-focused on cybersecurity. The importance of vigilance on this front cannot be overstated. And, as courts begin to open and we again begin to focus on litigation, in the legal department, consider whether your organization’s workforce, now scattered across various geographies, may give rise to unique litigation issues related to personal jurisdiction.

XII. A Theme Emerged in a Year of Crisis

A theme emerged in the last eighteen months: when in crisis – even when we are all in the same crisis – a company’s best emergency response strategies will be personalized to the organization. In 2020 and 2021, as the globe weathered the same health crisis, those organizations that invested in tactics specific to their needs, their weaknesses, and their strengths found success. A crisis’s impetus may be the same for many, but your organization’s best response must narrowly-tailored to your business. Applying a working understanding of crisis management tactics, like this quick reference guide, and adapting it to account for your organization’s particular positioning in the marketplace is the first step to cultivating a robust crisis management strategy.

View Article

Back